|

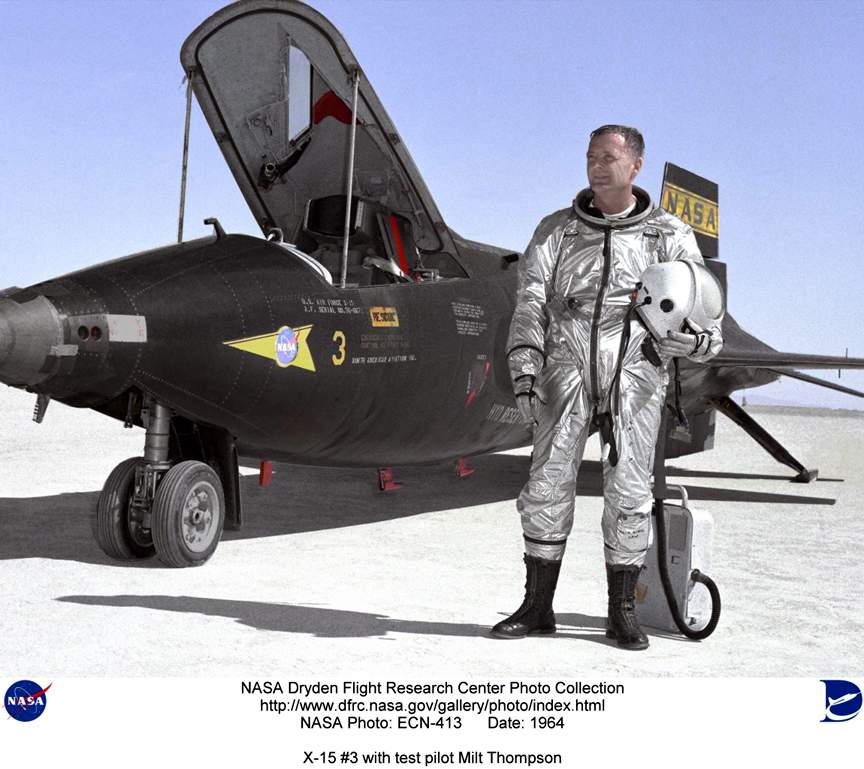

Milton 0. Thompson was

a research pilot, Chief Engineer and Director of Research Projects during

a long career at the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center. Thompson was

hired as an engineer at the flight research facility on March 19, 1956,

when it was still under the auspices of the NACA. He became a research

pilot in January 1958.

On August 16, 1963 Thompson became the first person to

fly a lifting body, the lightweight M2-F1. The plywood and steel-tubing

prototype was flown as a glider after releasing from an R4D tow plane.

He flew it a total of 47 times, and also made the first five flights of

the all-metal M2-F2 lifting body, beginning July 12, 1966.

Lifting bodies were wingless vehicles designed to generate

lift and aerodynamic stability from the shape of their bodies. They were

flown at Dryden to study and validate the concept of safely maneuvering

and landing a low lift-over-drag vehicle designed for reentry from space.

Data from the program helped in the development of the Space Shuttles.

Thompson was also one of the 12 NASA, Air Force, and

Navy pilots to fly the X-15 rocket-powered research aircraft between 1959

and 1968. He began flying X-15s on October 29, 1963, only a couple months

after his first Lifting Body flight. He flew the aircraft 14 times during

the following two years, reaching a maximum speed of 3712 mph (Mach 5.48)

and a peak altitude of 214,100 feet on separate flights.

| Les vols de Milton Thompson |

| N° du vol |

Pilote |

Date |

Vitesse (Mach) |

Altitude (m) |

Remarque |

| 1-40-64 |

|

29/10/63 |

4.10 |

22.677 |

Premier vol de Thompson |

| 3-24-41 |

Thompson |

27/11/63 |

4.94 |

27.371 |

_ |

| 3-25-42 |

Thompson |

16/01/64 |

4.92 |

21.641 |

_ |

| 3-26-43 |

Thompson |

19/02/64 |

5.29 |

23.957 |

_ |

| 3-29-48 |

Thompson |

21/05/64 |

2.90 |

19.568 |

_ |

| 3-32-53 |

Thompson |

12/08/64 |

5.24 |

24.750 |

_ |

| 3-34-55 |

Thompson |

03/09/64 |

5.35 |

23.957 |

_ |

| 3-36-59 |

Thompson |

30/10/64 |

4.66 |

25.586 |

_ |

| 3-37-60 |

Thompson |

09/12/64 |

5.42 |

28.163 |

_ |

| 3-39-62 |

Thompson |

13/01/65 |

5.48 |

30.297 |

_ |

| 1-54-88 |

Thompson |

25/05/65 |

4.87 |

54.803 |

_ |

| 1-55-89 |

Thompson |

17/06/65 |

5.14 |

33.071 |

_ |

| 1-56-93 |

Thompson |

06/08/65 |

5.15 |

31.455 |

_ |

| 1-57-96 |

Thompson |

25/08/65 |

5.11 |

65.258 |

_ |

The X-15 program provided a wealth of data on aerodynamics,

thermodynamics, propulsion, flight controls, and the physiological aspects

of high-speed, high-altitude flight.

In 1962, Thompson was selected by the Air Force to be

the only civilian test pilot to fly in the X-20 Dyna-Soar program that

was intended to launch a human into Earth orbit and recover with a horizontal

ground landing. The program was canceled before construction of the vehicle

began.

Thompson concluded his active flying career in 1967,

becoming Chief of Research Projects two years later. In 1975 he was appointed

Chief Engineer and retained the position until his death on August 6,

1993.

Thompson was also a member of NASA's Space Transportation

System Technology Steering Committee during the 1970s. In this role he

was successful in leading the effort to design the Orbiters for power-off

landings rather than increase weight with air-breathing engines for airliner-type

landings. His committee work earned him NASA's highest award, the Distinguished

Service Medal.

Born in Crookston, Minn., on May 4, 1926, Thompson began

flying with the U.S. Navy as a pilot trainee at the age of 19. He subsequently

served during World War II with duty in China and Japan.

Following six years of active naval service, Thompson

entered the University of Washington, in Seattle, Wash. He graduated in

1953 with a Bachelor of Science degree in Engineering. He remained in

the Naval Reserves during college, and continued flying—not only naval

aircraft but crop dusters and forest-spraying aircraft.

After college graduation, Thompson became a flight test

engineer for the Boeing Aircraft Company in Seattle. During his two years

at Boeing, he flew on the sister aircraft of Dryden's B-52B air-launch

vehicle.

Thompson was a member of the Society of Experimental

Test Pilots, and received the organization's Iven C. Kincheloe trophy

as the Outstanding Experimental Test Pilot of 1966 for his research flights

in the M2 lifting bodies. He also received the 1967 Octave Chanute award

from the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics for his lifting-body

research.

In 1990, the National Aeronautics Association selected

Thompson as one of the year's recipients of its Elder Statesman of Aviation

awards. The awards have been presented each year since 1955 to individuals

for contributions "of significant value over a period of years" in the

field of aeronautics.

Thompson wrote several technical papers, was a member

of NASA's Senior Executive Service, and received several NASA awards.

Joseph A. Walker was a Chief

Research Pilot at the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center during the mid-1960s.

He joined the NACA in March 1945, and served as project pilot at the Edwards

flight research facility on such pioneering research projects as the D-558-1,

D-558-2, X-1, X-3, X-4, X-5, and the X-15. He also flew programs involving

the F-100, F-101, F-102, F-104, and the B-47.

Walker made the first NASA X-15 flight on March 25, 1960.

He flew the research aircraft 24 times and achieved its fastest speed

and highest altitude. He attained a speed of 4,104 mph (Mach 5.92) during

a flight on June 27, 1962, and reached an altitude of 354,300 feet on

August 22, 1963 (his last X-15 flight).

He was the first man to pilot the Lunar Landing Research

Vehicle (LLRV) that was used to develop piloting and operational techniques

for lunar landings. Walker was born February 20, 1921, in Washington,

Pa. He lived there until graduating from Washington and Jefferson College

in 1942, with a B.A. degree in Physics. During World War II he flew P-38

fighters for the Air Force, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross and

the Air Medal with Seven Oak Clusters.

| Les vols de Joseph Walker |

| N° du vol |

Pilote |

Date |

Vitesse (Mach) |

Altitude (m) |

Remarque |

| |

Walker |

25/03/60 |

2.00 |

14.822 |

1er vol NASA et de

Walker. |

| |

Walker |

19/04/60 |

2.56 |

18.134 |

vol de familiarisation |

| |

Walker |

12/05/60 |

3.19 |

23.738 |

Record de vitesse

non officiel |

| |

Walker |

04/08/60 |

3.31 |

23.809 |

Le record de vitesse

du X-2 est battu |

| |

Walker |

19/08/60 |

3.13 |

23.159 |

Etude de l'échauffement

aérodynamique |

| |

Walker |

30/03/61 |

3.95 |

51.694 |

Difficulté

d'allumage du XLR-99, nouveau record d'altitude |

| |

Walker |

25/05/61 |

4.95 |

32.166 |

Nouveau record de

vitesse, panne du SAS |

| |

Walker |

12/09/61 |

5.21 |

34.839 |

Validation de modifications

sur la protection thermique des ailes |

| |

Walker |

17/10/61 |

5.74 |

33.101 |

Vol préparatoire

du record de vitesse (plus de 6000 km/h) |

| |

Walker |

19/04/62 |

5.69 |

46.940 |

Premier vol du X-15

n°1 avec SAS auxilliaire |

| |

Walker |

30/04/62 |

4.94 |

75.195 |

Nouveau record absolu

d'altitude |

| 1-29-50 |

Walker |

07/06/62 |

5.39 |

31.577 |

_ |

| |

Walker |

27/06/62 |

5.92 |

37.704 |

Préparation

du record d'altitude, record absolu de vitesse sur X-15A |

| 1-31-52 |

Walker |

16/07/62 |

5.37 |

32.674 |

_ |

| 3-8-16 |

Walker |

02/08/62 |

5.07 |

44.044 |

_ |

| 3-9-18 |

Walker |

14/08/62 |

5.25 |

59.010 |

_ |

| 3-13-23 |

Walker |

20/12/62 |

5.73 |

48.890 |

_ |

| |

Walker |

17/01/63 |

5.47 |

82.814 |

Vol spatial (>80

km) |

| 3-15-25 |

Walker |

18/04/63 |

5.51 |

28.194 |

_ |

| 3-16-26 |

Walker |

02/05/63 |

4.73 |

63.825 |

_ |

| 3-18-29 |

Walker |

29/05/63 |

5.52 |

28.041 |

_ |

| 1-36-57 |

Walker |

25/06/63 |

5.51 |

34.077 |

_ |

| 1-37-59 |

Walker |

09/07/63 |

5.07 |

69.007 |

_ |

| |

Walker |

19/07/63 |

5.50 |

106.009 |

Deuxième vol

spatial de Walker |

| |

Walker |

22/08/63 |

5.58 |

107.960 |

Record absolu d'altitude,

25ème et dernier vol de Walker, test d'un altimètre |

Walker was the recipient of many awards during his 21

years as a research pilot. These include the 1961 Robert J. Collier Trophy,

1961 Harmon International Trophy for Aviators, the 1961 Kincheloe Award

and 1961 Octave Chanute Award. He received an honorary Doctor of Aeronautical

Sciences degree from his alma mater in June of 1962. Walker was named

Pilot of the Year in 1963 by the National Pilots Association.

He was a charter member of the Society of Experimental

Test Pilots, and one of the first to be designated a Fellow. He was fatally

injured on June 8, 1966, in a mid-air collision between an F-104 he was

piloting and the XB-70.

Major General "Bob" White,

USAF, began his military career like many another feisty American teenager

in World War II. Eager to serve his country as a fighter pilot, he entered

the Army as an eighteen-year-old aviation cadet in November, 1942. In

spite of the wartime tempo gripping the entire nation, military flight

training throughout the war was thorough and painstaking, giving new American

pilots far more flying experience than their Axis enemies. It was not

until February, 1944, that he won his coveted pilot's wings and was commissioned

a Second Lieutenant in the Army Air Forces. Fighter training followed,

and Lt White finally joined the 354th Fighter Squadron of the

355th Fighter Group (Eighth Air Force) in England in July,

1944.

The group, which had been newly-equipped with high-powered

P-51 Mustang fighter planes, was flying bomber escort missions over Germany.

After the Normandy landings and the Allied breakout at St. Lo, Lt White

and his comrades also flew ground attack missions to cut enemy supply

lines, as well as carrying out fighter sweeps against the Luftwaffe. He

continued this hazardous flying until February, 1945, when he was shot

down by heavy antiaircraft fire over Germany during his 52nd

combat mission. He was captured, and remained a prisoner of war until

his prison camp was liberated two months later.

Peace And War Again

Following the victory, he returned to the United States

and enrolled as a student at New York University, where he received a

Bachelor of Science degree in electrical engineering in 1951. During his

student years, White remained a member of the Air Force Reserve at Mitchel

Air Force Base in New York, where his old squadron had transferred after

the war. The crisis in Korea soon intruded however, and his first college

degree was no sooner in hand than he found himself recalled to active

duty in May, 1951. Back in uniform, he first served as a pilot and engineering

officer with the 514th Troop Carrier Wing at Mitchel AFB. In

February 1952, however, he was sent to Japan and assigned to the 40th

Fighter Squadron as an F-80 pilot and flight commander until the summer

of 1953.

The Scientific Pilot

Facing a crossroads in his career at the end of the Korean

War, the youthful fighter pilot elected to remain on active duty and turned

his steps to the advancement of scientific flight. From a system engineer's

job at the Rome Air Development Center in New York, he soon traveled to

California to attend the Air Force's Experimental Test Pilot School at

Edwards AFB. Captain White graduated with Class 54C in January, 1955,

and stayed on at Edwards as a working test pilot, flying and evaluating

advanced models of the F-86K Sabre, F-89H Scorpion, and the new F-102

Delta Dart and the F-105B Thunderchief.

He became the Deputy Chief of the Flight Test Operations

Division, and somewhat later was named Assistant Chief of the Manned Spacecraft

Operations Branch.

Higher and Faster

His destiny was to change dramatically when the joint

Air Force-Navy-NASA X-15 project moved into high gear in 1958. This project,

designed to explore the problems connected with manned flight beyond the

earth's atmosphere, required the world's most advanced research airplane

to study the physical effects of flight at unprecedented speeds and altitudes.

The solution was the X-15; North American Aviation's futuristic rocket-powered

research aircraft, launched from a B-52 mother ship, was designed to probe

to the very boundaries of atmospheric flight and beyond, and to yield

invaluable data for the nation's developing space program.

Now a Major with well-honed flying and technical skills,

White was designated the Air Force's primary pilot for the X-15 program

in 1958. While the new plane was undergoing its initial tests, he attended

the Air Command and Staff College at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama,

graduating in 1959. He then made his first X-15 flight on April 15, 1960,

when the new aircraft was still fitted with only two small (16,000 lbs.

total thrust) interim rocket engines. Four months later, still using the

temporary engines, he took the experimental craft to an altitude of 136,000

feet above Rogers Dry Lake bed.

| Les vols de Bob White |

| N° du vol |

Pilote |

Date |

Vitesse (Mach) |

Altitude (m) |

Remarque |

| |

White |

13/04/60 |

1.94 |

14.630 |

1er vol

de White |

| |

White |

06/05/60 |

2.20 |

18.574 |

Vol de familiarisation,

difficultés de largage de la dérive inférieure |

| |

White |

19/05/60 |

2.31 |

33.222 |

Premier vol d'altitude,

étude des conditions de rentrée dans l'atmosphère

|

| |

White |

12/08/60 |

2.52 |

41.605 |

Record d'altitude |

| |

White |

07/02/61 |

3.50 |

23.820 |

Nouveau record absolu

de vitesse |

| |

White |

07/03/61 |

4.43 |

23.607 |

Mission inaugurale

des vols d'études avec XLR-99, nouveau record de vitesse |

| |

White |

21/04/61 |

4.62 |

32.004 |

Nouveau record de

vitesse |

| |

White |

23/06/61 |

5.27 |

32.827 |

Nouveau record de

vitesse, premier franchissement de Mach 5 |

| |

White |

11/10/61 |

5.21 |

66.142 |

Nouveau record d'altitude |

| |

White |

09/11/61 |

6.04 |

30.968 |

Nouveau record de

vitesse |

| |

White |

01/06/62 |

5.42 |

40.416 |

Premier vol du X-15

n°2 avec SAS auxilliaire |

| 3-5-9 |

White |

12/06/62 |

5.02 |

56.266 |

_ |

| |

White |

21/06/62 |

5.08 |

75.194 |

_ |

| |

White |

17/07/62 |

5.45 |

95.936 |

Premier vol spatial,

nouveau record d'altitude |

| |

White |

14/12/62 |

5.65 |

43.100 |

Quatorzième

et dernière mission de White |

Thus began the series of flights reaching blazing speeds

and altitudes which would soon earn the engineer-pilot high public exposure

as well as professional acclaim. After the craft's 57,000 lb thrust YLR-99

engine was installed, he flew it to a speed of 2,275 mph in February,

1961, setting an unofficial world speed record. Over the next eight months,

he became the first human to fly at Mach 4 and then at Mach 5. This amazing

rise climaxed on November 9, when White reached a speed of 4,093 mph.

This was 93 mph more than the plane was designed to achieve and made White

the first human to fly a winged craft six times faster than the speed

of sound. Following this he took the X-15 to a record-setting altitude

of 314,750 feet on July 17, 1962, more than 59 miles above the earth's

surface.

Flying at this altitude also qualified him for astronaut

wings, and he became the first of the tiny handful of "Winged Astronauts"

to achieve that coveted status without using a conventional spacecraft.

President John F. Kennedy used the occasion to confer the most prestigious

award in American aviation, the Robert J. Collier Trophy, jointly to White

and three of his fellow X-15 pilots; NASA's Joseph Walker, CDR Forrest

S. Peterson of the U.S. Navy, and North American Aviation test pilot Scott

Crossfield. A day later, Air Force Chief of Staff General Curtis E. LeMay

awarded Major White his new rating as a Command Pilot Astronaut.

The research pilot also received the National Aeronautics

and Space Administration's Distinguished Service Medal and the Harmon

International Trophy from the Ligue Internationale des Aviateurs for the

most outstanding contribution to aviation for the year. Perhaps the most

meaningful award to a test pilot, however, came from his peers: the Society

of Experimental Test Pilot's Iven C. Kincheloe Award. None of these honors

come a pilot's way for the mere breaking of flight records which was,

after all, part of the very nature of the research program. Rather, they

were professional recognition of his sustained and outstanding accomplishments

in increasing human knowledge about the world of flight.

For all of the drama of high-performance research flight,

however, White was still a line pilot in the Air Force. In October 1963,

he returnedto the site of some of his wartime exploits in Germany, this

time as operations officer for the 36th Tactical Fighter Wing

at Bitburg. Next, he achieved what most Air Force pilots consider to be

the peak of a military career: command of an operational fighter squadron.

He remained in command of the 53d Tactical Fighter Squadron until he returned

to the United States in August, 1965. Then it was time to return to the

classroom, this time to the Industrial College of the Armed Forces in

Washington, where he graduated in 1966. That same year, he received a

Master of Science degree in business administration from The George Washington

University. An assignment to the Air Force Systems Command (AFSC) followed,

as Chief of the Tactical Systems Office, F-111 Systems Program Office

at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio.

To War Again

Then, for the third time in his career, war intervened.

In May, 1967, he went to Southeast Asia as Deputy Commander for Operations

of the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing, stationed at Takhli Royal

Thai Air Force Base in Thailand. The wing was flying F-105 Thunderchief

tactical bombers, and during his assignment he flew 70 combat missions

over North Vietnam. In October he was then transferred to Seventh Air

Force Headquarters at Tan Son Nhut Airfield, Republic of Vietnam, where

he served as Chief of the Attack Division in the Directorate of Combat

Operations.

Research and Development

Then it was time to return to the world of research and

development, and in June, 1968, he went back to Wright-Patterson AFB and

AFSC, this time as Director of the Aeronautical Systems Division's F-15

Systems Program Office. Now a full Colonel, he was responsible for managing

the development and production planning of the new F-15 Eagle weapons

system, the air-superiority fighter which would enter the Air Force inventory

in the mid-1970s and see the nation into the 21st Century.

Return to Edwards AFB

Colonel White's next assignment brought him back to Edwards

AFB. Designated a selectee for the rank of Brigadier General, the 46-year-old

officer assumed command of the Air Force Flight Test Center on July 31,

1970. A wide range of responsibilities came with this position: overseeing

the research and developmental flight testing of both manned and unmanned

aircraft and aerospace vehicles, and ensuring the continued operation

of the Air Force Test Pilot School, to say nothing of the supervision

of the Air Force's second-largest base and several thousand military and

civilian personnel. A number of important testing programs were already

underway:

Category II testing of the A-7D close air support plane,

numerous system evaluations of the F-111 and FB-111A tactical bomber,

and combined Category I-II testing of the immense C-5A Galaxy transport.

During General White's command, evaluation began of a number of other

aircraft vital to the Air Force in years to come: The F-15 Air Superiority

Fighter, the A-X ground attack aircraft (eventually to become the A-10

of Gulf War fame), and the revolutionary E-3A Airborne Warning and Control

Systems (AWACS) aircraft. In addition to his other duties during his tenure,

General White completed the Naval Test Parachutist course and was awarded

his parachutist's wings in October, 1971.

Final Flights

General White served at the Flight Test Center until

October 17, 1972. The following month, he assumed the duties of Commandant,

Air Force Reserve Officer's Training Corps. In February, 1975, he won

his second star and in March became Chief of Staff of the Fourth Allied

Tactical Air Force.

Robert M. White retired from active duty with the Air

Force as a Major General, in February, 1981. |